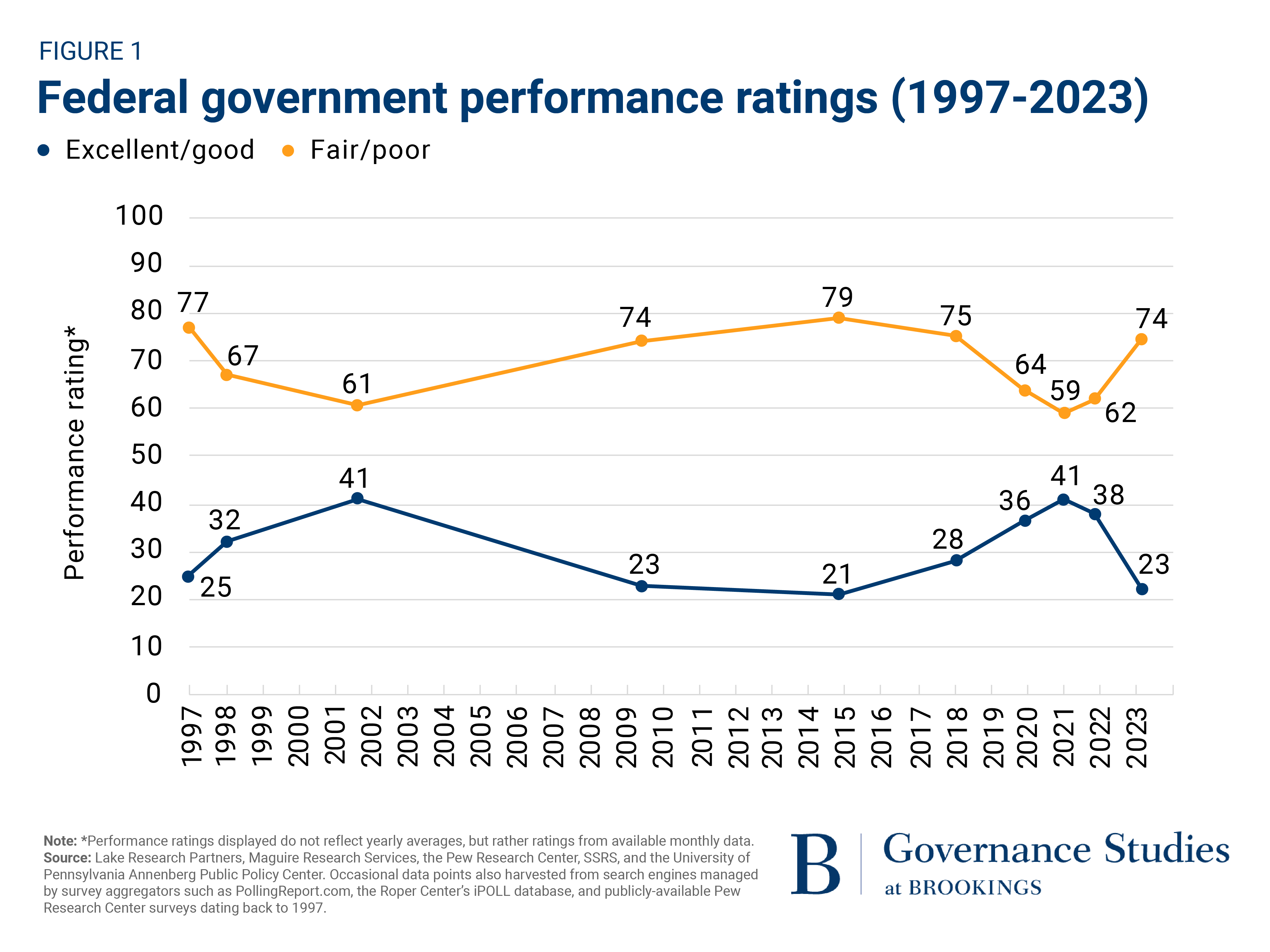

President Biden heads toward the 2024 campaign with the federal government’s job rating in decline, support for a smaller government increasing, and the demand for major government reform at a 30-year high. Biden not only needs to reverse the recent drop in his job rating for running government, but he must also repair the bureaucratic damage Trump left behind and prevent further government breakdowns on his watch. [1]

As Figure 1 suggests, Biden must also confront the partisan divisions in the federal government’s performance marks. Interviewed in January 2023, 40% of Democratic respondents gave the federal government an excellent/good rating, compared to just 7% of Republicans. Although the two parties shared hints of common ground with 40% of Democrats and 61% of Republicans in favor of very major government reform, the preferences for bigger and smaller government provide little encouragement.

As this report suggests, Americans already support Biden’s “Plan to Guarantee Government Works for the People” and its long-needed campaign finance reform. At the same time, they also want an end to government breakdowns, faster service at federal offices, and easy access to online portals. The good news for Biden is an already-vetted list of government reforms that can be enacted and implemented well before November 2024; the bad news is that he has already faced ten government breakdowns on his watch with more likely to come.

Biden launched his 2020 presidential campaign with a deep divide between respondents who favored a bigger government providing more services versus a smaller government providing fewer services. As Figure 2 shows, 50% of respondents surveyed in August 2020 favored a bigger government providing more services, while 43% favored a smaller government providing fewer services.

Further analysis shows a significant party impact on the size of government questions. Interviewed in early 2023, 49% of Democrats, 27% of independents, and just 31% of Republicans favored a bigger government providing more services, while just 14% of Democrats, 29% of independents, and 67% of Republicans favored a smaller government providing fewer services.

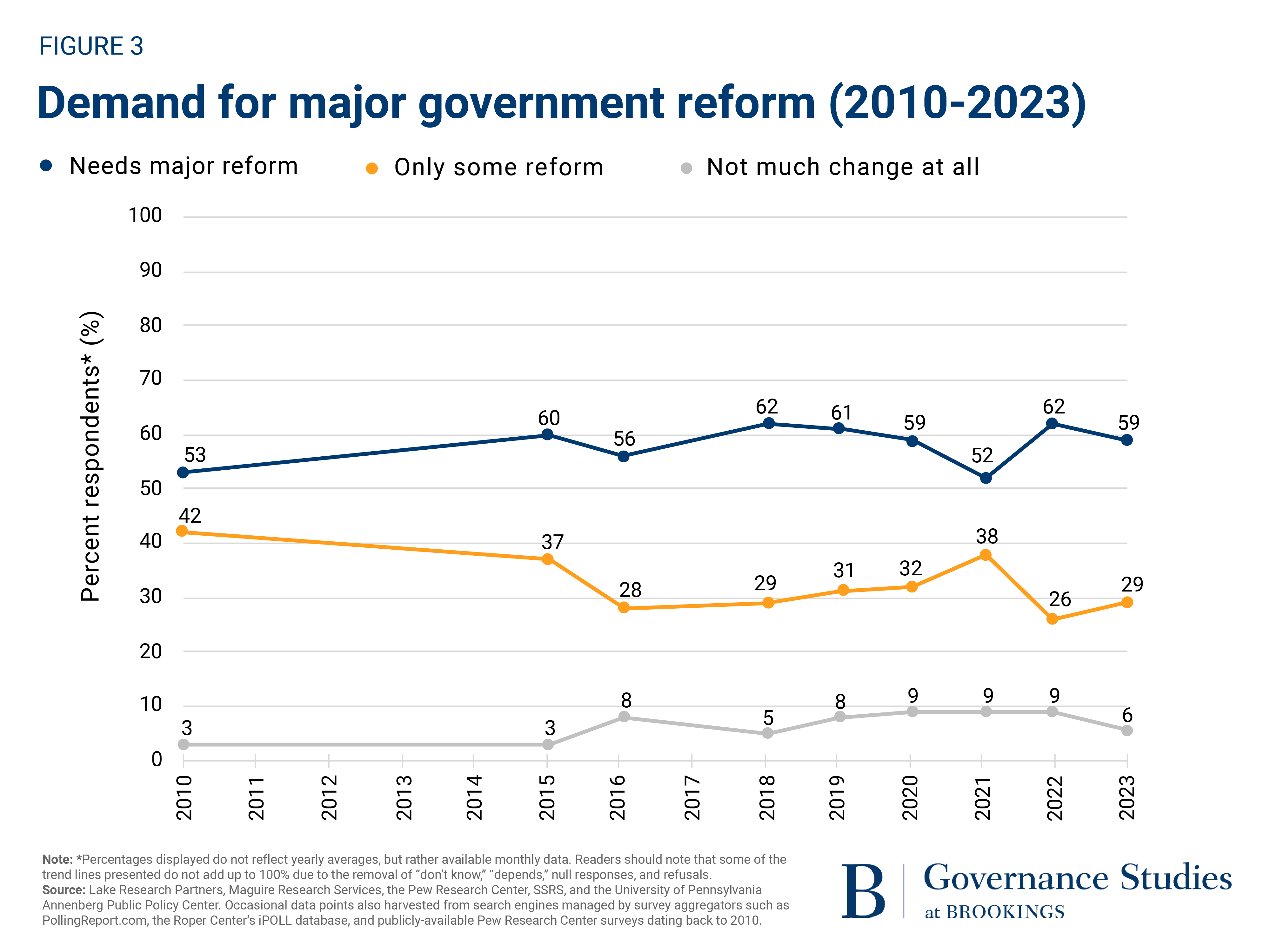

As demonstrated in Figure 3, the demand for major government reform has increased since 1990, when the first surveys by the Pew Research Center were conducted. Driven by familiar divisions on overspending, economic performance, globalization, and social issues, partisans’ demand for reform often wanes when their party holds the presidency:

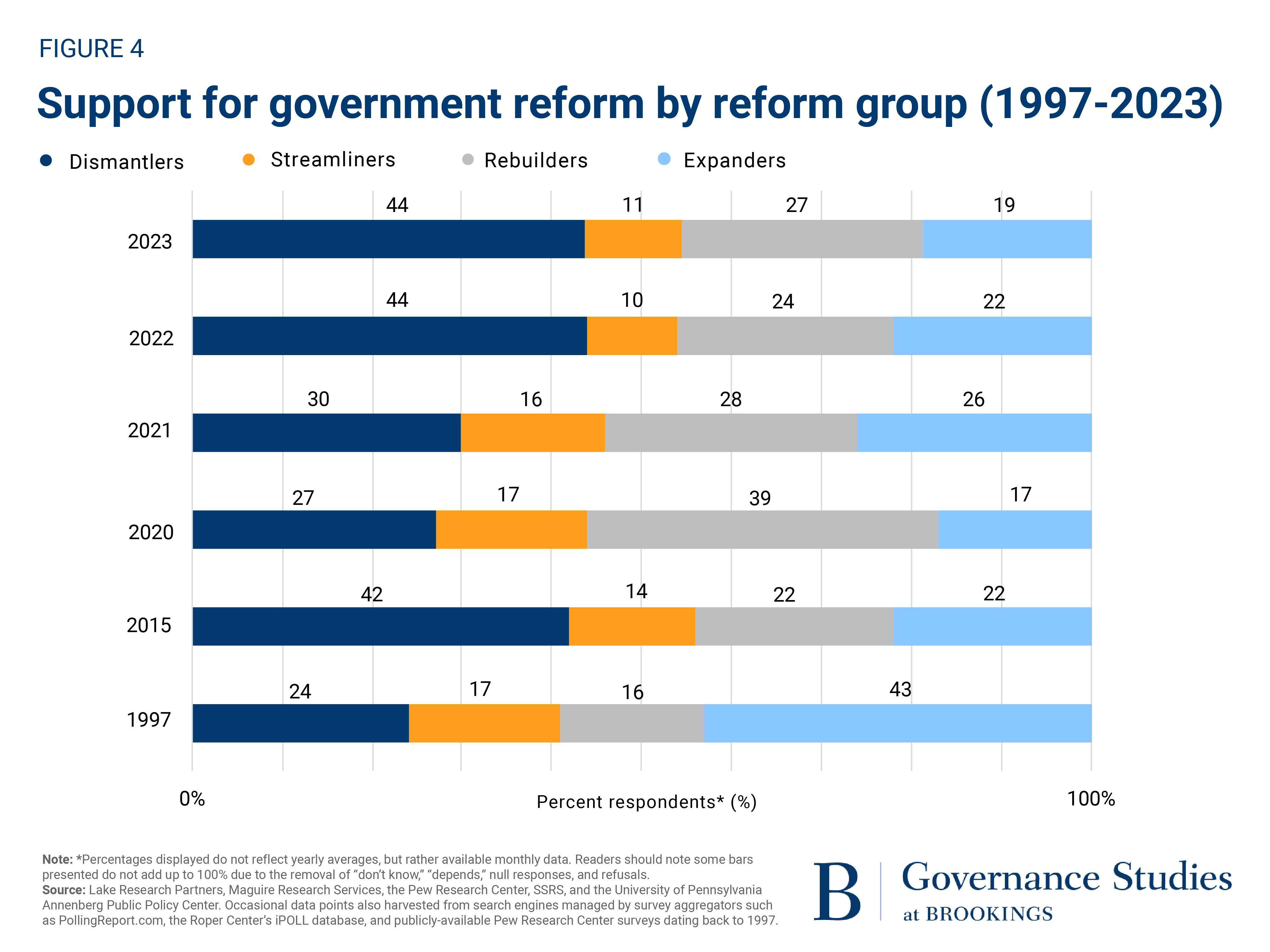

As Figure 4 suggests, public support for bigger or smaller government combines with demand for reform to create four reform positions for further analysis. The left column of the chart focuses on the size of government—large or small—while the top row focuses on the need for reform—very major or only some. Each of the four positions has its precedents:

Although respondents were not questioned on support for each position separately, Figure 5 provides a reasonable distribution built on public support for bigger/smaller government and demand for very major/only some reform. According to my analysis of the January 2023 SSRS survey of 1,000 randomly selected respondents, 44% of respondents supported dismantling, 27% “expanding,” 19% “rebuilding,” and 11% “streamlining.”

Like the “the tides of government reform” that generate new laws, rules, executive orders, and occasional blue-ribbon commissions, each of the four positions outlined in Figure 4 generates its campaign promises and slogans. Jimmy Carter focused on streamlining in calling for a competent, compassionate, lean, and tight government; Al Gore on rebuilding in promising a government that works better and costs less; Donald Trump on dismantling in promising to “cut so much your head will spin;” and Biden on expanding in committing to his “build-back-better” agenda.

Looking back to the 1990s when the Pew Research Center first asked its bigger/smaller government question, Republicans have led the call for a smaller government providing fewer services, while Democrats have pushed for a bigger government that provides more services. Despite continued demand for major government reform during his first two years in office, Biden has yet to embrace a reform agenda that might bring small-government streamliners and reform-minded rebuilders together on government reform. Meanwhile, the percentage of dismantlers grew from just 24% in 1997 to 44% in 2023, while the percentage of expanders fell from 43% to just 19%.

As Figure 5 shows, dismantlers accounted for 44% of Republicans in April 2022 with streamliners in second position at 22%, while rebuilders accounted for 42% of Democrats with expanders in second position at 26%. Hard as the two political parties work to expand their bases, neither can win without holding their core support.

Even if the number of Biden expanders grows along the way to the 2024 election, he must address the negative public opinion toward the federal government and the 77% of respondents who recently told the Pew Research Center that “dealing with federal government agencies is often not worth the trouble;” the 63% who said the “federal government does a poor job responding to the needs of ordinary citizens;” and the 72% who said the federal government is not careful with taxpayer money. Biden needs a reform agenda that addresses these doubts.

As Figure 6 shows, the dismantlers gave Biden his lowest job ratings for running the federal government and its programs in January 2023, while the expanders gave Biden his highest ratings. Facing continued pressure to improve government performance, Biden might find inspiration in Vice President Gore’s 1993 promise to make government “cool again.” Although his commitment to reinventing government was not enough to secure the presidency, his focus on $400 government hammers, imminently breakable ashtrays, and $600 toilet seats gave him the government reform visibility that Biden needs to address the recent surge in government breakdowns on his watch.

Biden still has time to strengthen his job ratings and reclaim the popularity he enjoyed earlier in his presidency but will need to stop the government breakdowns that deplete public confidence in his governing ability. As show in Figure 7, Biden finished his first June in the White House with a 50% excellent/good rating for running the federal government’s programs but lost ground in every survey over his first year before hitting 30% in January 2023.

Biden’s early job ratings were largely driven by his promise to repair a broken presidency, but the following analysis suggests that Biden must also put government reform high on his agenda. At least for now, however, he has largely ignored the nuts and bolts of bureaucratic repair. Having inherited a dispirited bureaucracy from Donald Trump, his policy agenda has largely eclipsed his commitment to the major reform that a solid majority of Americans support.

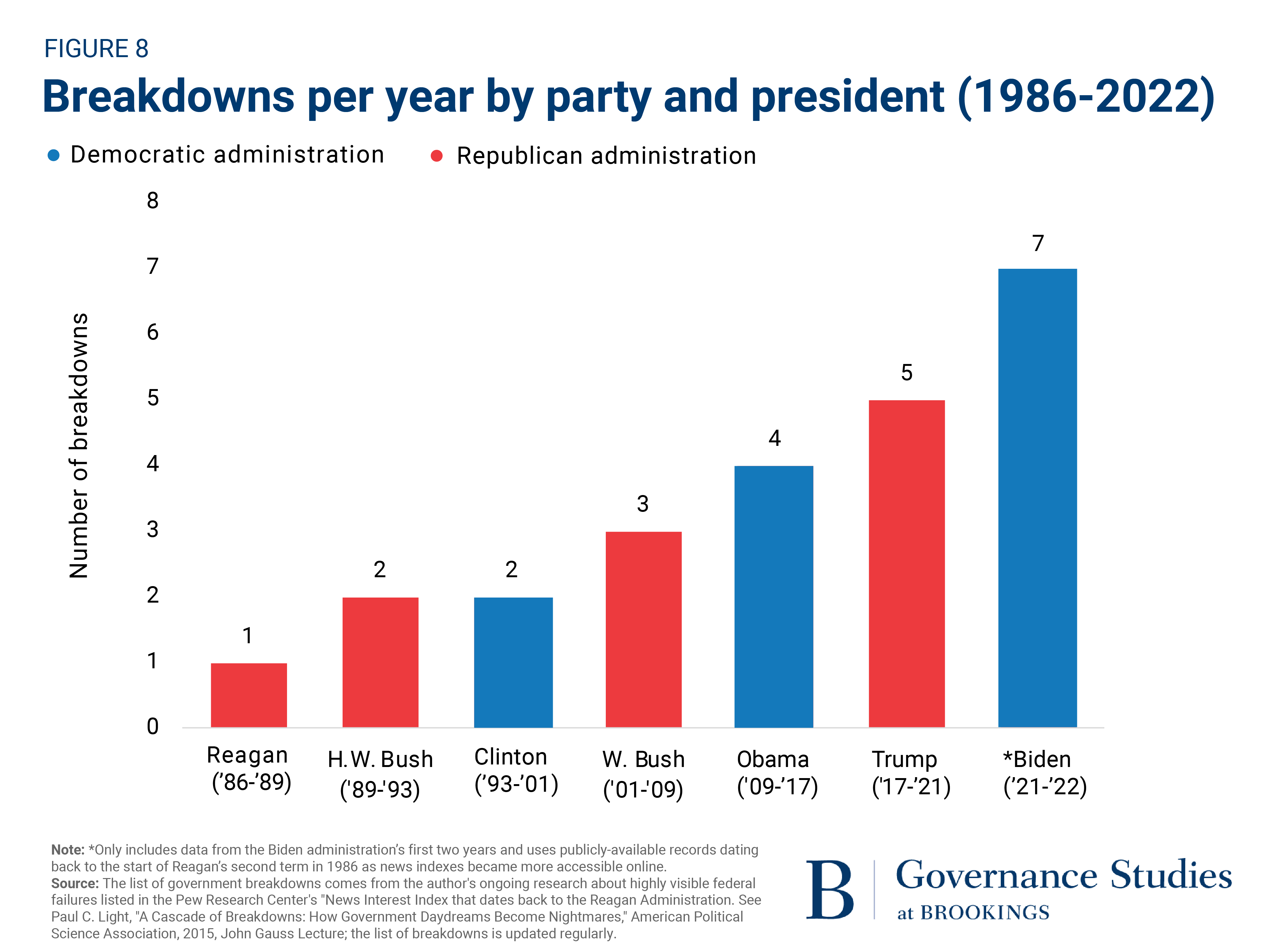

Like presidents before him, Biden’s job ratings are linked to government breakdowns. Defined as a visible failure with high levels of public interest, the recent increase in breakdowns per year strongly suggests the need for presidential leadership on long-needed repairs. As observed in Figure 8, every president since Reagan has added to the breakdown curve, including two per year under H.W. Bush, four under Obama, five under Trump, and six per year during Biden’s first two years in office. [2] It may not be something presidents like to do, but the absence of aggressive reform may be a harbinger of defeat.

According to my study of highly visible government breakdowns from 1985 to the present, most federal government breakdowns are caused by fragile policy designs, resource and staff shortages, antiquated technology, training deficits, technology glitches, bad luck, political interference, and bureaucratic sabotage, all of which relate to the erosion of what the Niskanen Center calls “state capacity.”

As the rising numbers of breakdowns suggest, breakdowns are almost always a product of pressure, neglect, and overconfidence. Instead of blaming presidents, legislators, contractors, lobbyists, and grifters for government failure, Congress and the president should address their general reluctance to move government repairs to the top of the legislative agenda. Figure 9 shows that Democrats and Republicans were at the wheel for equal numbers of breakdowns over time without a sign that they are ready to work together to reduce the risks in a bipartisan future.

The next generation of major reform may yet emerge from Biden’s White House chief of staff, Jeffrey Zients. Having served in senior leadership posts through the years, Zients will face little White House resistance should he embrace needed repairs at the Environmental Protection Agency, Federal Aviation Administration, Food and Drug Administration, and other broken agencies. If he can find a way to honor Biden’s $800 billion promise to soldiers exposed to burn pits overseas, he might even have enough time to rebuild the Internal Revenue Service. He has found common ground before after all.

Biden rarely misses a chance to highlight his service in the war on government fraud, waste, and abuse but has generally eschewed government reorganization. [3] This reluctance dates back to the 2008 presidential campaign when Barack Obama asked each of his vice presidential candidates if they would be “very happy to reorganize the government.” Biden left no doubt about his answer: “No, that’s not what I want to do.”

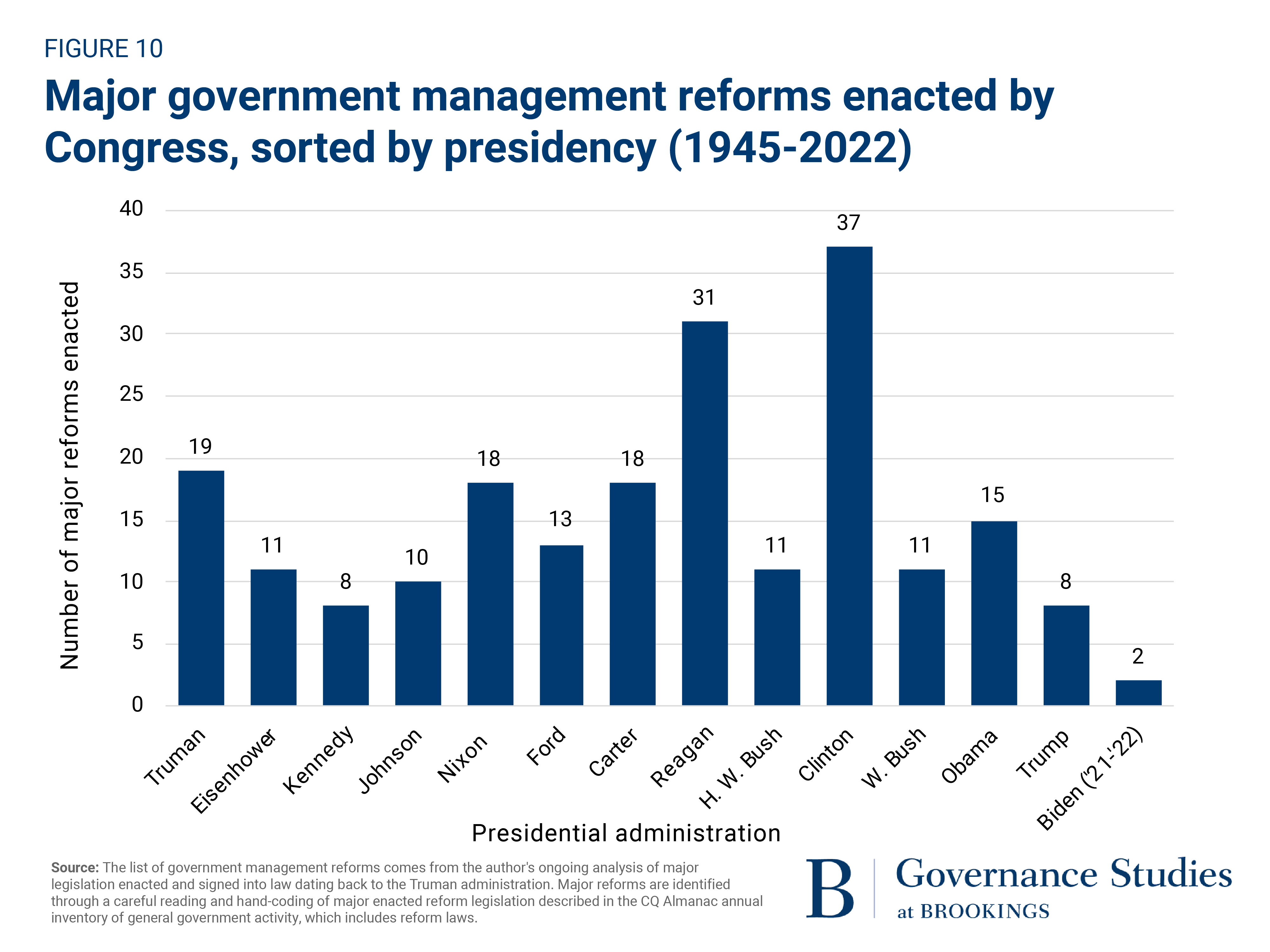

Biden and Congress may yet find common ground on bureaucratic reform as a bipartisan path to institutional comity. Figure 10 reveals that the number of large-scale management reforms fell sharply as the nation turned its attention to the war on terror and economic pressure. As Figure 11 also shows, the number of bureaucratic layers also surged as the federal government took a bureaucratic war setting. Boring as reform might be to policy insiders, a thorough review of federal management challenges could give Biden and Congress a welcome dose of comprehensive reform legislation. [4]

Biden still has time to rebuild his job ratings before the 2024 campaign but will almost certainly face further breakdowns that will highlight the need for bureaucratic repairs. Once described by Paul Krugman as the “big spender” America wants, Biden must now become the bureaucratic repairman the federal government desperately needs.

Toward this end, Biden should move quickly to flatten the bloated hierarchy, streamline the presidential appointments process, and modernize the rulemaking process, while making sure the blended federal workforce of 11 million active-duty military personnel, civil servants, contractors, grantees, and postal workers have the resources, systems, and leadership to succeed.

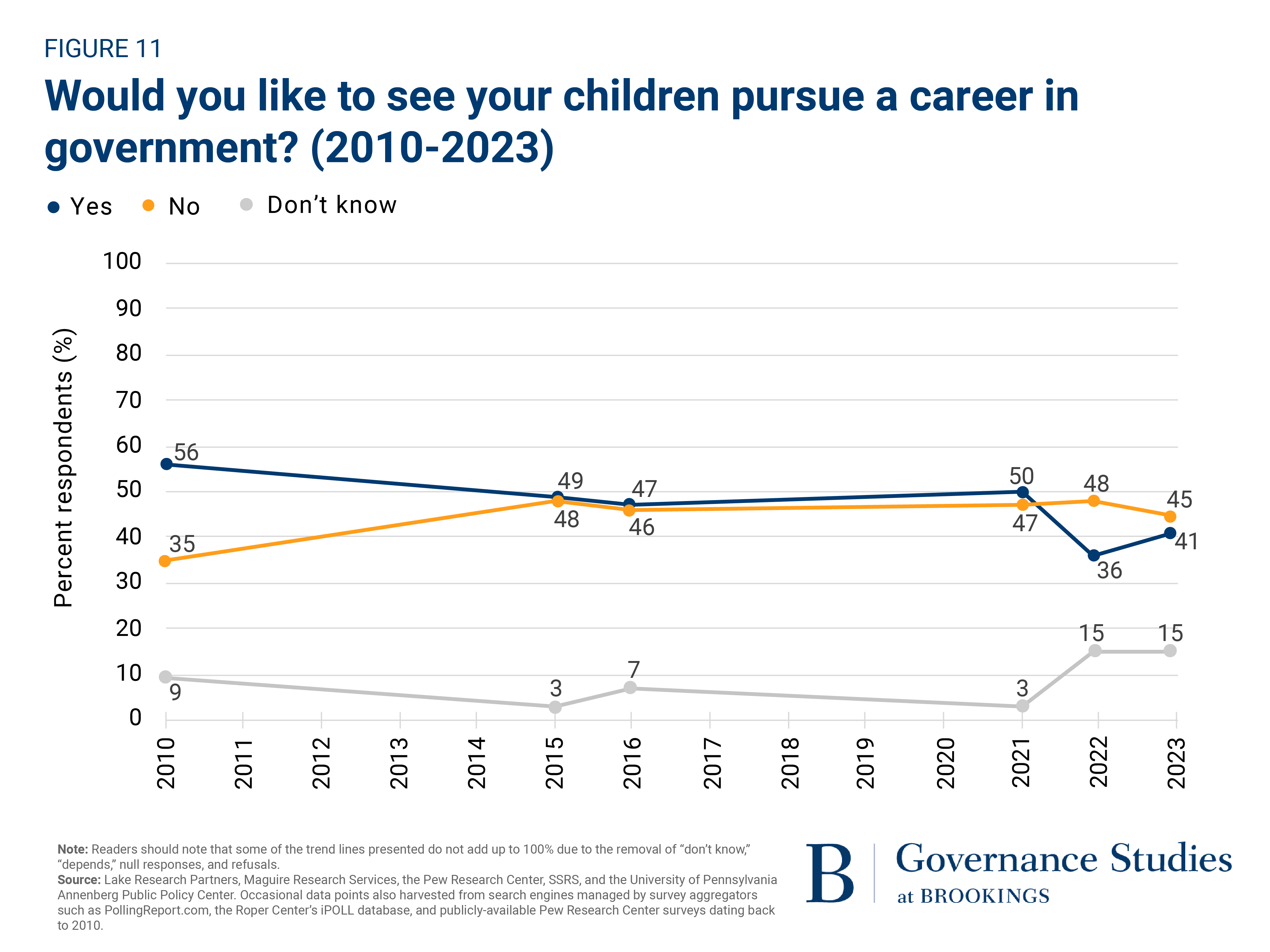

This broad assessment of what the nation wants from reform leads to an emerging crisis in government staffing as the baby boomers retire. As exhibited in Figure 11, the past 20 years of breakdowns, layering, and anti-government rhetoric have taken a toll on student interest in government careers and parental support. Asked whether they would recommend a career in government to a son or daughter, the percentage of respondents who say “yes” has been falling since 1997.

In turn, the percentage of those who said “no” has held steady in the 40% range since 1997, while the percentage of those who had no recommendation at all also held steady in the single digits. Figure 11 shows that the percentage of “don’t know” responses to the question more than doubled from just 6% in 1997 to 15% in 2023, pushing the total number of “don’t know” and just plain “no” responses to 60%.

Readers should note the potential impact of the January 6 insurrection on parental support for government careers in the percentages of “don’t know” answers. They might also consider the role of partisanship in shaping support for government performance, given the 56% of Democrats who said “yes” to a career in government for a son or daughter compared with the 62% of Republicans who said “no.”

Biden has been a critic of government waste dating back to his 2011 “Campaign to Cut Waste.” Having claimed the nickname, “Sheriff Joe,” for cutting waste in Obama’s $900 billion stimulus package, Biden promised another war on waste in 2021 as his $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan took shape. Although the plan contained funds for fraud prevention, the federal government was still catching up to the COVID-19 stimulus bill when the Biden package began spending as a “particularly fertile target for fraudsters.”

Biden does not need a new generation of fraud-busters and inspectors general to succeed, though he does need to rebuild the investigatory workforce after Trump’s resistance to oversight. Instead, he needs to find enough congressional support to fix broken systems once identified, reverse staffing shortages, and corral the technology and training that promote success.

If the past is prologue, Biden will face more government breakdowns in the future, including risks that could match the pandemic delays and the bloody Abbey Gate bombing. Government reorganization may not be what Biden wanted to do, but he may soon discover that it is his best ticket to a second term.

This analysis clearly demonstrates the potential impact of government reform on Biden’s 2024 success. Having largely avoided blue-ribbon reform commissions and study groups during his tenure in office, Biden may yet discover the value of road-tested slogans such as Jimmy Carter’s “government as good as its people” and Al Gore’s “government that works better and costs less.” To quote one of his favorite sayings, Biden needs to “finish the job” that Carter and Gore began years ago.

Biden must also recognize the sharp limits of government reform. Even as he hopes for shorter lines at the Transportation Security Administration, faster service from Obamacare, and more clarity from the Internal Revenue Service, the dismantlers and streamliners are more likely to ridicule Biden’s promise to “put people at the center of everything the government does.” Absent a significant commitment to government reform, many Americans might wonder whether being at the center of everything is too close for comfort.

[1] The public opinion trend lines presented in this report come from random-sample surveys conducted by Lake Research Partners, Maguire Research Services, the Pew Research Center, SSRS, and the University of Pennsylvania Annenberg Public Policy Center, some of which were funded by the author of this study. Additional survey findings came from searchable survey aggregators such as PollingReport.com, the Roper Center’s iPOLL database, and the Pew Research Center.

All survey findings discussed in this report are based on random-sample surveys of 1,000 randomly selected respondents interviewed by cell phone and landline with estimated error rates of 3% to 4% at a 95% confidence level. Readers should note that some of the trend lines presented in this report do not add up to 100% due to the removal of “don’t know,” “depends,” null responses, and refusals from the final tallies.

The Pew Research Center’s survey trends were particularly important in anchoring the four data points that yield key findings on what Americans want from reform:

For a sample of Pew Research Center data points extracted for this report, see the Center’s Deconstructing Distrust report and its “Decades of Distrust” update. Biden’s job ratings for running the federal government and its programs came from random-sample surveys of 1,000 respondents conducted by cellphone and landline by McGuire Research from June 2021 to January 2023. The 2023 trend extensions came from a January 2023 Maguire Research Service telephone survey of 1,000 randomly selected respondents contacted by random digit dialing. The margin of error in the survey results is plus or minus 3%. (Back to top)

[2] The government breakdown list is built upon publicly available histories, news reports, and other archival materials used to track federal government events dating back to the start of Reagan’s second term in 1986. Based in part on inventories of highly visible stories recorded by Pew Research Center, each breakdown in the inventory had to meet three tests to reach the list discussed in this report: (1) high visibility in the news, (2) high levels of public interest in response, and (3) evidence of federal government management or policy failure. The first ten breakdowns on Trump’s 2018-2019 watch are listed first below and followed by the first ten breakdowns on Biden’s 2021-2022 watch. Readers should note that the Trump and Biden lists cover the first ten breakdowns at the start of their presidencies. (Back to top)

Breakdowns on Donald Trump’s watch, 2017 – 2020

Year

News interest