In the realm of genetic testing, insurance payers have been reluctant to recognize that there is a method of testing that gives physicians over 99% of the information that they need to solve current or even future medical puzzles related to genetics.

When evaluating insurance policies, it’s important to know that whole genome sequencing (WGS) offers the most comprehensive testing available providing granular, actionable data from an individual’s DNA to diagnose and effectively treat many inherited disorders, including inherited cancers.

With WGS the individual’s entire DNA is scanned. Because upwards of 99% of the individual’s genetic information is available, physicians are able to comprehensively evaluate and effectively pinpoint and/or rule out the precise genetic cause of the patient’s disease. All as part of a single, once and done test that eliminates the prolonged “diagnostic odyssey” that often delays a definitive genetic diagnosis, sometimes as much as decades.

In addition, the data from WGS can be reused again and again, throughout an individual’s lifetime, any time a new medical situation presents. There’s no need to collect another sample for additional testing.

The Human Genome Project gave us the “transformative textbook of medicine” by mapping and categorizing the approximately 20,500 genes that make up the human “genome.”

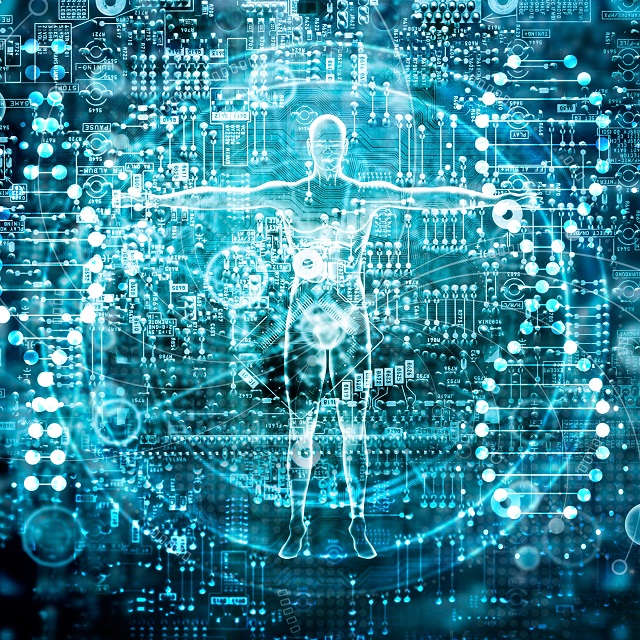

You could reasonably conclude that the ability of WGS to provide access to an individual’s genetic blueprint throughout one’s entire life would be a rather good example of doing things right the first time and would, therefore, be an attractive addition to the medical benefits offered by insurance payers. Especially as the technology for conducting WGS has become so much less expensive in recent years. Yet, there are very few insurers that cover whole genome sequencing. Why is this?

One reason is that, in the United States, there is no uniform way that insurers are evaluating the types of sophisticated WGS testing technologies now available. When you look at corporate policies, even when carriers cover less comprehensive genetic tests, like whole exome, there’s little consistency in the way they make their decisions.

The Latest

Listen to free podcasts to get the info you need to solve business challenges!

The evidence for supporting such tests is out there for all carriers, yet some say “Yes, we’ll cover it” while others say “No, we won’t” — all while citing the same studies as the basis of their conflicting coverage decisions. When insurers do cover WGS, it tends to be “rapid” WGS for critically ill NICU patients. The value of WGS is recognized in this time-critical environment, while it is simultaneously dismissed as experimental for pediatric and adult patients who would similarly benefit.

Inadequacies in detail regarding procedure and reimbursement coding is often described as a second barrier to coverage because it hinders insurance companies from easily evaluating what type of genetic test was performed and whether that test was warranted. To be fair, this can be said about most tests that are being reimbursed today. Yes, it might be difficult and laborious to evaluate, but coding for molecular genetic testing, like WGS, needs to become more granular.

More insurers are using genetic benefit managers and lab benefit managers to act as gatekeepers for advanced genetic tests and they are requiring more information upfront on what tests are being provided. As the codes become more descriptive and additional information is more routinely submitted, managers will be able to make more accurate reimbursement decisions.

Some medical directors continue to cling to outdated views of genetic testing, denying WGS coverage despite a continuous stream of supporting clinical validation studies.

One of the most common misconceptions is that widely available, low cost, direct-to-consumer genetic tests provide all the information that an individual could need about their genome. In most cases, the technologies used for these tests are in no way equivalent to WGS — covering only a fraction of the individual’s DNA. When an individual requires diagnosis of an inherited disorder, direct-to-consumer tests are not a substitute for the insurance provider’s genetic testing policy.

What is most needed is education along with a uniform framework and guideline that insurers work from to evaluate whether to cover a technology or not. The data supporting WGS is out there. More clinical cases are being resolved thanks to its use, many of which have fallen through the cracks of the system following multiple costly, less comprehensive genetic tests. Physicians are seeing this and are quicker to acknowledge the utility of these tests and to introduce them into their testing arsenal.

It is widely known and accepted that that when physicians are able to make decisions about what is applicable and appropriate for patients, better outcomes follow. Until coverage and reimbursement of WGS becomes commonplace, if you want to ensure access to top-notch health care, it will continue to be important to take a close look at the carrier’s approach to genetic testing when evaluating insurance policies.

Daryl Spinner is vice president of market access and reimbursement for Variantyx, a genome sequencing company.